This article has been written for Easy History by Hannah Latham

Introduction

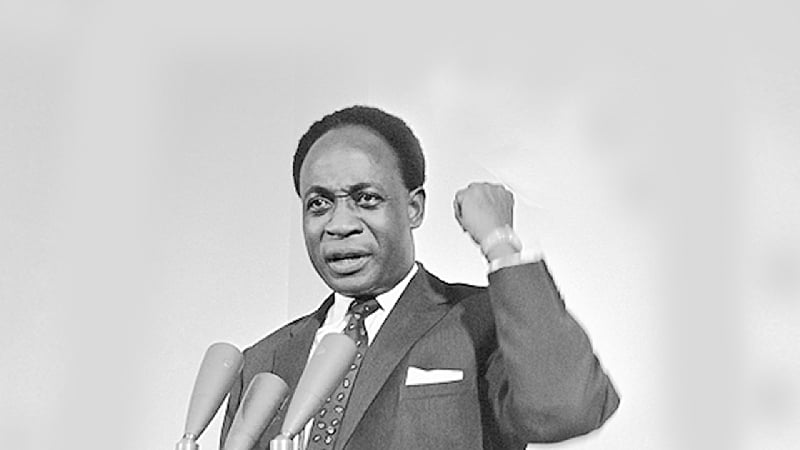

Kwame Nkrumah emerged as a pioneering figure, leading Ghana (formerly the Gold Coast) to become the first sub-Saharan African country to achieve independence in 1957 and establish the Republic of Ghana in 1960. With this, he set out to establish a unified and centralised government aiming to promote national cohesion. His time in power has been investigated heavily by historians. Nkrumah is remembered and celebrated for his accomplishments in founding Ghana but criticised for his later failures. He was a driving factor in ending colonial rule and advancing Pan-Africanism not just in Ghana but in the whole African state. However, he created difficulties with many unsuccessful economic reforms and was central to the introduction of authoritarianism in Ghana which skyrocketed his unpopularity.

Nkrumah’s successes

Nkrumah’s political success is associated with the ending of colonial rule in Ghana and his role in the Pan Africanism movement. He wrote of a ‘new Africa’, a reconstructed society rising from the ruins of imperialism, colonialism and neo-colonialism, with Africans united by bonds of humanism and egalitarianism. Throughout some of his key speeches this Pan-Africanism message and anti-colonialist view resonated throughout. On Ghana’s Independence Day in 1957, he celebrated his country for becoming “free forever” noting that the ‘independence of Ghana is meaningless unless it is linked to the

total liberation of Africa’. This demonstrates his eagerness to unite Africa. This Pan Africanism led to his central role in the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1963. The idea was for the organisation to seek to harmonise relations between the young states emerging from the colonial experience, to defend their newly

won sovereignty and to extend the emancipation movement. This grew to bring together 32 newly independent African states. Addressing the Heads of Independent African state at the formation of the OAU in Addis Ababa, Nkrumah reinforced his advocacy for Pan Africanism. He explained how colonialism had been holding Africa back and explained how they could mobilise to improve life for the people. He emphasises the nations must “unite” and indicated that “the people of Africa call for the breaking down of boundaries that keep them apart” . This highlights his eagerness to push Pan-Africanism unity.

Nkrumah is celebrated for projecting Ghana into political force on the world stage. This was carried out with Ghana’s involvement in a series of conferences. In his Independence Day speech of 1957, he emphasised the movement for Africans in politics to demonstrate their “own African personality and identity” to show the world that “we are ready for our own battles”. This began with the Conference of Independent States in April 1958, and the All-African People’s Conference held in December of the same year. In 1959, representatives of African trade unions met in Accra to found the All-African Trade Union Federation. Ghana also played an important role in organising the All-African People’s Conference in Cairo in 1961. This was notable for the establishment and maintenance of networks, associations, and connections with other African movements in many countries, for which Nkrumah propelled. This showcased his ability to mobilise African countries around a shared vision of unity, independence and economic cooperation. Nkrumah positioned Ghana as a vanguard of African leadership.

Nkrumah’s shortfalls

Nkrumah’s handling of the opposition during his time of power is one of his main criticisms. He used the increasing opposition to eliminate political dissenters, ensuring his concentration of power within his party, the Convention People’s Party (CPP). He is heavily criticised for the implementation of the Preventative Detention Act in 1958 which

empowered the government to arrest and detain political opponents without trial. This led to Nkrumah allowing the absorption of labour unions and producers associations within the CPP. The 1958 Industrial Relations Act created 24 official unions and subordinated them to the Trade Union Congress (TUC) which in turn was subordinated to the Party. This eventually led to the CPP banning strikes. By 1962, Nkrumah formally declared that village level organisations including those led by chiefs would be absorbed into the Party, and by this time, Ghana had become a corporatist, de facto one-party state. This undermined the ideals of freedom and democracy that were central to the struggle for independence. Writing in his book Consciencism in 1964 he noted that “a one-party system is better able to express and satisfy the common aspirations of a nation as a whole”. This demonstrates the basis of his ideals, which led to widespread discontent. Nkrumah, who had based the independence movement on the idea of “freedom”, had begun to limit this for his own population.

Nkrumah’s economic plans were largely unsuccessful. This new political state allowed Nkrumah to construct a new Seven Year Plan as a basis for aggressive economic growth. He decided that Ghana needed a big push towards industrialisation, launching the Plan in 1964. In his speech launching the Seven Year Plan he noted how it “will bring Ghana to the threshold of a modern state based on a highly organised and efficient agricultural and industrial programme. This Seven Year Plan was based on investments totaling about £1,000 million, a huge figure considering Ghana’s GDP was

estimated in 1960 at £469 million. However, his heavy focus on industrialisation, combined with poor planning, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and a collapse of cocoa prices plunged Ghana into debt. Despite Nkrumah’s vision for a new industrialised Ghana, it is clear that the plan was overambitious. This became apparent in the dissatisfaction grown against his rule, and he was later overthrown in a coup. This highlights how Nkrumah’s plans for Ghana were poorly executed and resulted in his loss of power, a clear indication of ”failure”.

Conclusion

Historian Davidson summarises Nkrumah’s importance in leading Ghana to political independence but explains how he “struggled with the greater problems of making economic progress” . Throughout this discussion this has become evident: Nkrumah while progressive and largely responsible for Ghana and later Africa’s independence, made graver mistakes with corruption and economic plans. Nkrumah represents the key successes and structural limitations of the first nationalist generation within Africa. While visionary in pushing for the granting of independence, he did not successfully secure a long term and stable political and economic future for Ghana.

Primary Sources:

- Nkrumah, Kwame: ‘at Long Last, the Battle Has Ended!’ Independence Day – 1957.

- Nkrumah, Kwame. Consciencism. – 1978

Secondary Sources:

- Apter, David E. “Ghana’s Independence: Triumph and Paradox.” Transition, no. 9 (2008)

- Haynes, Jeffrey. Review of Kwame Nkrumah and African Liberation, by Henry L.

- Bretton, Basil Davidson, and Trevor Jones. Third World Quarterly 10, no. 1 (1988)

- Rooney, David. “INTRODUCTION.” In Kwame Nkrumah. Vision and Tragedy, 9–12 Sub-Saharan Publishers, 1988

About the Author:

Hannah Latham is a final year student at Queen Mary University of London studying History. She particularly loves researching the Cold War. She enjoys writing in her spare time, aspiring to work in the publishing and journalism industries post-graduation.

Leave a Reply